A crash course in computer Cache

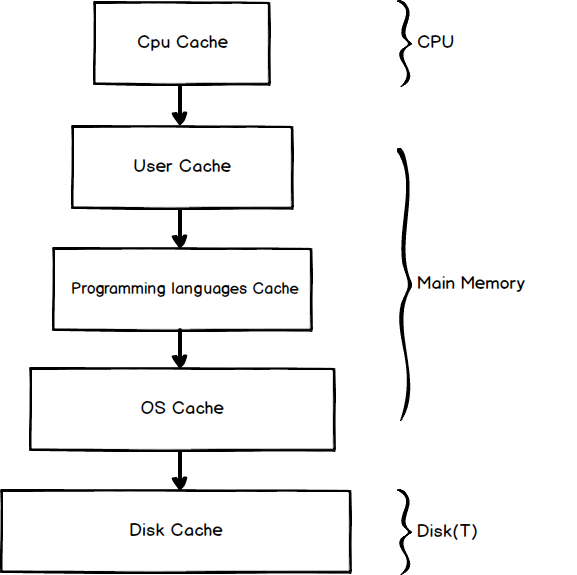

Even though the computer run much faster then we expected nowadays, the speed between the different components are still very large. To solve this problem, we introduce different levels of caches. After access the data from storage, we store the most used (temporal locality) and the nearby data (spatial locality) in the current lever so we can aceesee them directly later. The term storage here is relative. For example, main memory is a storage to CPU cache, and the disk is a storage to main memory. When running a program, it may reach several levels of caches. Let’s look closer to it:

CPU cache

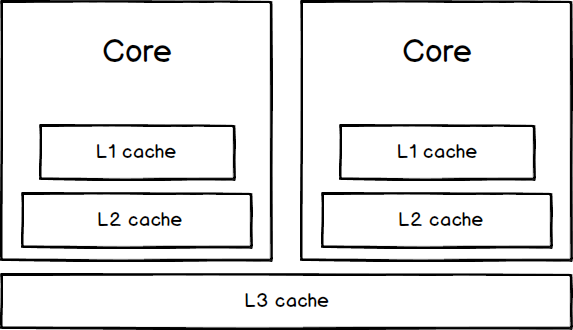

CPU built a pyramid-like cache architecture, each of them keeps a small piece of data and instructions in it.

Every data or instruction form different kinds of applications may cache by the CPU cache which programmers can’t control. For more details, you may have a look at How L1 and L2 CPU Caches Work.

User cache

Generally speaking, User cache is the most used cache form programmers. When we use a hashmap or dictionary to store some data for future use. User cache comes to our eyes. Here is a Python example to use cache or not for calculating the nth Fibonacci numbers:

# code without cache

def fibonacci(n):

if n <= 1:

return n

return fibonacci(n-2) + fibonacci(n-1)

# code with cache

dic = {}

def fibonacci(n):

if n in dic:

return dic[n]

if n <= 1:

return n

dic[n] = fibonacci(n-2) + fibonacci(n-1)

return dic[n]

With the help of the User cache, the time complexity of this problem drop from O(2**n) to O(n) which save a huge of time when n is large.

Program languages cache

Since calling system call like read() or write() repeatedly in user space is expensive, some program languages try to avoid this by keeping a small piece of cache inside. The I/O module in Python use a small buffer (8 1024 bytes by default) to store some temporary data. When we try to read some data from f* using:

# Python code

f.read(10)

Python will search the data from its read buffer to see if the data already in it before calling a raw system call read(), we will show more details in the later capter.

OS cache

Disk I/O may be the slowest part of our computer. Therefore, after access the data from the disk, the OS system will keep the hotspot data (Which its size is dynamic) in main memory (In Linux, it called Page cache). Moreover, we can use a mechanism called virtual memory to swap this data to disk temporary if not enough main memory is available now.

Linux supports virtual memory, that is, using a disk as an extension of RAM so that the effective size of usable memory grows correspondingly. The kernel will write the contents of a currently unused block of memory to the hard disk so that the memory can be used for another purpose. When the original contents are needed again, they are read back into memory

Disk buffer

Disk also has its own way to speed up. Even though we use fsync() in our code, it doesn’t mean the data already written to the disk safely.

Calling fsync() does not necessarily ensure that the entry in the

directory containing the file has also reached disk. For that an

explicit fsync() on a file descriptor for the directory is also

needed.

Different kind of caches lookup

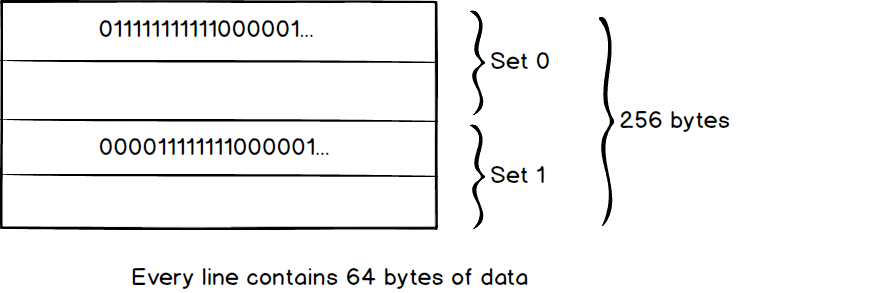

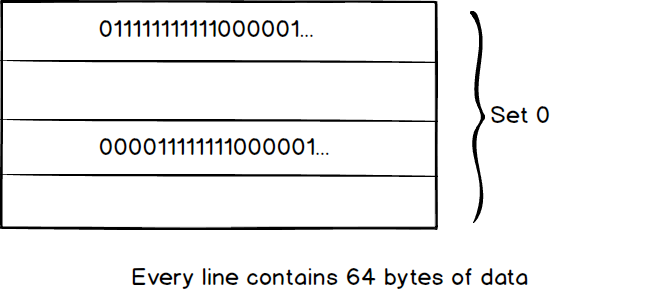

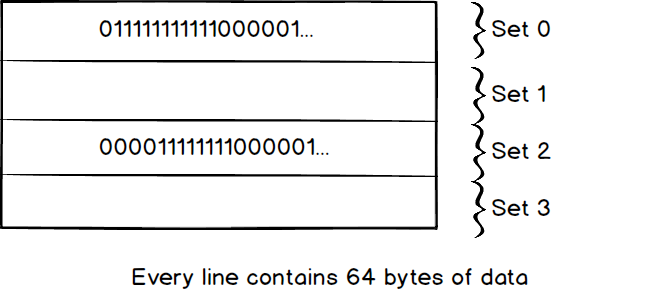

The data search policy in cache is quite straightforward. We search the data from the top to the bottom. Let’s dive into the deep to see how a computer actually looks up the data in the cache. There is three popular way to do this nowadays. Set Associative, Fully Associative and Direct Mapped. Luckily, the last two just a special case of Set Associative (Direct Mapped ≈ 1-way set Associative, Fully Associative ≈ N-way set associative). Here is a small 256 bytes cache which divides by four lines, every line contains 64 bytes (We call it 2-way 2 set associative because we have 2 sets and each set contains 2 lines in the cache).

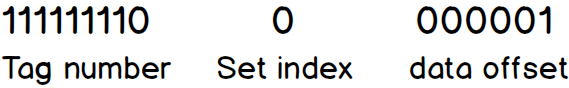

When we want to read data from OxFF01 (Ob1111111100000001 in binary), First we divide the address into a different part

The first part is the tag number, every line in the cache also has its own tag number, when the tag number in the address matches the one in the cache, that means we found the correct address to read/write data. The second part is set index used to identify which set the address belongs to. The last part is the data offset in the line. The search policy is quite simple:

- Search the set in the cache depend on the address’s set index ( which is 0 in this case).

- Search if the tag number in the lines belongs to the set. If yes, (in our case cache hit) return the data depends on data offset. If no, cache miss.

We used a 2-way 2 sets associative in this example, Can we do better than it? Well, first let’s imagine, if we only use one set for the cache.

we have to compare the tag number in each line from the top to bottom which would be slow in large cache. This is how Fully Associative works. Second, it looks like the search would be faster with more and more set. How about we create n set which n equals to the number of lines.

Great idea! This leads us to Direct Mapped, Direct Mapped is the quickest way to search data in the cache. However, there is a problem here, as we know, the cache is always smaller than the storage. If the storage is 10 times bigger than the cache. 10 locations in the storage will map to the same location. When we write data to the location, there is a high probability that we have to overwrite other useful data which map to the same lines. The problem will get worse when the storage is much bigger than the cache.

Set associative is a tradeoff, Set associative use multiple sets to narrow the search range, in the example, When we use 4 sets, we can do a search inside the set 0 which would be 4 times faster then Fully Associative. When we write the data to the cache, we can just write the data to the same set reduce conflict.

Cache Policy

When we found the data in the cache, we call it cache hit, otherwise cache miss. The computer also has to decide what should do after a cache miss.

| x | cache miss | |

|---|---|---|

| Read through | read data from storage, update the cache, return data to caller | |

| Write through | write data to the cache and the storange | |

| Write Around | write data to the storage directly | |

| Write back | writes data to the cache, marking them as dirty, after some delay, it writes the data back to the storange |